j'ai grandi dans une petite ville du Limousin.

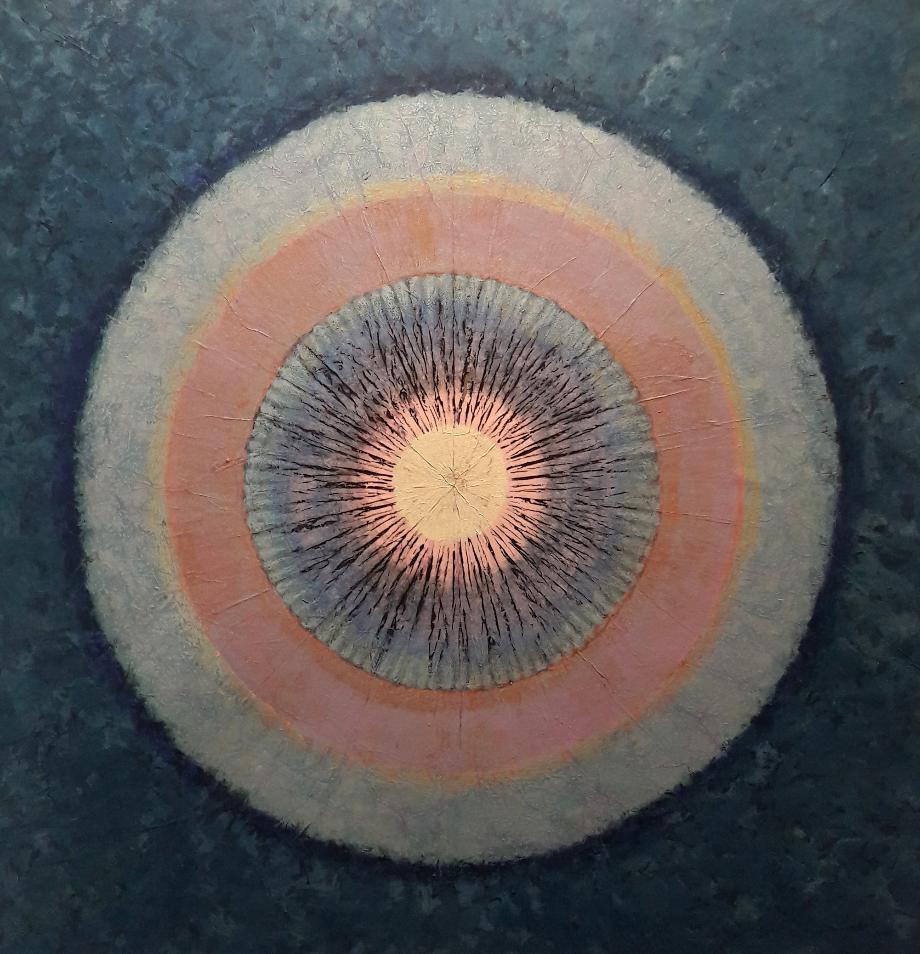

Leurs fonds aux teintes naturelles révèlent les encres obtenues de plantes ou de fleurs après un bain à l’eau oxydée.

et quelques mots fondateurs :

une

nouvelle de B. Traven m'accompagne,

découvrez-la ici,

cela vaut la peine de prendre le temps de la lire,

hymne à la lenteur, au temps présent,

aux fabrications faites mains et cœur...

bonne lecture,

I'd like you to discover a story from B. Traven: Assembly Line,

find the english version at the end of the french one.

Chaîne de montage - 1966

M.E.L. Winthrop, de New York, était en vacances dans la république du

Mexique. Quelques temps auparavant, il s’était avisé que ce pays

étrange et vraiment sauvage n’avait pas encore été exploré complètement

et de façon satisfaisante par les Rotariens et les Lions1,

qui sont toujours conscients de leur glorieuse mission terrestre, ce

pourquoi il avait estimé de son devoir de bon citoyen américain de

faire ce qu’il pouvait pour réparer cette négligence.

Cherchant les occasions de satisfaire sa nouvelle vocation, il se tenait à l’écart des sentiers battus et s’aventurait dans des régions qui n’étaient pas indiquées ni, a fortiori, recommandées aux touristes étrangers par les agences de voyages. C’est ainsi qu’un jour il se trouva dans un bizarre petit village indien de l’Etat d’Oaxaca.

En suivant, à pied, la grand-rue poussiéreuse de ce pueblecito2 qui ignorait le pavage, le drainage, la plomberie et l’éclairage artificiel (mise à part la chandelle), il rencontra un Indien accroupi sur le seuil de terre battue d’une hutte de palmes appelée jacalito. L’Indien était en train de confectionner de petits paniers au moyen de toutes sortes de fibres qu’il avait ramassées dans l’immense forêt entourant le village de toutes parts. Ces matériaux avaient été non seulement soigneusement préparés par le vannier mais aussi richement colorés au moyen de teintures extraites par lui de diverses plantes, écorces et racines, voire de certains insectes, selon un procédé connu de lui seul et des siens.

Ce n’était point là, pourtant, sa principale activité. Cet homme était un paysan qui vivait de ce que sa terre, petite et peu fertile, lui procurait au prix de beaucoup de labeur, de beaucoup de sueur et d’incessants soucis concernant la pluie. Le soleil, le vent et le rapport des forces sans cesse changeant entre les oiseaux et les insectes bénéfiques ou nuisibles. Il faisait des paniers lorsqu’il n’avait rien d’autre à faire dans les champs, car il détestait rester inoccupé, et la vente desdits paniers, si limitée fût-elle, augmentait d’autant son modeste revenu.

Bien qu’il ne fût qu’un simple paysan, il suffisait de voir ses petits paniers pour deviner qu’il était aussi un artiste véritable et accompli. Chaque panier paraissait orné des plus extraordinaires dessins de fleurs, de papillons, d’oiseaux, d’écureuils, d’antilopes et de tigres. Le plus surprenant était que ces décorations multicolores n’étaient pas peintes sur les paniers mais tressées avec une habilité incomparable, sans que l’homme s’inspirât d’un dessin ou d’un modèle quelconque. A mesure que son travail avançait, les motifs apparaissaient comme par magie, mais il était impossible de deviner ce qu’ils représentaient aussi longtemps que le panier n’était pas entièrement achevé.

Les gens qui les achetaient au marché de la petite ville voisine s’en servaient comme corbeilles à couture, pour orner leur table ou l’appui des fenêtres, ou pour y ranger de petites choses. Les femmes y mettaient leurs bijoux, des fleurs ou de petites poupées. Ils avaient mille usages. Chaque fois que l’indien en avait confectionné une vingtaine, il les emportait à la ville, le jour du marché. Pour cela, il lui fallait parfois se mettre en route au milieu de la nuit, car il ne possédait qu’un âne et si, comme il arrivait souvent, son âne s’était égaré la veille, il devait faire la route à pied, dans les deux sens.

Au marché, il avait à payer vingt centavos de taxe pour pouvoir vendre ses paniers. Chacun de ceux-ci lui demandait de vingt à trente heures de travail, sans compter le temps qu’il avait passé à recueillir les fibres, à les préparer, à les teindre – et il les vendait cinquante centavos, l’équivalent de quatre cents Américains. Il arrivait rarement que l’amateur ne marchandât pas, en reprochant à l’Indien d’en demander un prix aussi élevé :

« Après tout, disait-il, ce n’est jamais que de la vulgaire paille de petate3, comme on en trouve partout dans la jungle... Et à quoi peut servir un si petit panier ? Tu devrais être déjà bien heureux que je t’en donne dix centavos, voleur ! Enfin, je suis dans un de mes bons jours : je serai généreux, je t’en donne vingt, à prendre ou à laisser... »

L’Indien finissait par en obtenir vingt-cinq, sur quoi l’acheteur s’exclamait :

« Quel ennui ! Je n’ai que vingt centavos de monnaie... Peux-tu me faire la monnaie d’un billet de vingt pesos ? »

Bien entendu, il n’en était pas question, et l’indien devait se contenter des vingt centavos... S’il avait eu la moindre connaissance du monde, il aurait su que ce qui lui arrivait, arrivait chaque jour à chaque artiste de chaque pays, et cela lui eût peut-être donné la fierté de savoir qu’il appartenait à cette petite armée qui est le sel de la terre4 et qui empêche la culture, la civilisation et la beauté de disparaître de ce monde...

Souvent aussi il n’arrivait pas à vendre tous ses paniers, car les gens, là comme ailleurs, préféraient les choses faites à la chaîne et toutes identiques entre elles. Lui, en revanche, qui avait confectionné plusieurs centaines de paniers et de corbeilles, tous ravissants, n’en avait pas fait deux qui fussent identiques. Chacun était une œuvre d’art unique en son genre, chacun était aussi différent des autres qu’un Murillo d’un Velasquez. Naturellement, il se refusait à rapporter chez lui ceux qu’il n’avait pas pu vendre et, en pareil cas, il allait les proposer de porte en porte, ce qui lui valait d’être traité tantôt comme un mendiant et tantôt comme un vagabond en quête de mauvais coups. Enfin, après qu’il eut marché longtemps, frappé à de nombreuses portes et essuyé pas mal d’injures ou de réflexions désagréables, une femme parfois l’arrêtait, lui prenait un panier et lui en offrait dix centavos, après quoi, sous ses yeux, elle jetait négligemment la petite merveille sur une table avec l’air de dire :

« Si je t’achète cet objet absurde, c’est uniquement par charité, parce que je suis chrétienne et que cela m’attriste de voir un pauvre Indien mourir de faim loin de son village... »

Cette pensée en appelant une autre, il arrivait qu’elle ajoutât à haute voix :

« Au fait, d’où viens-tu, Indito ? De Huehuetonoc ? Ecoute, ne pourrais-tu pas m’apporter deux ou trois dindes de ton pueblo, dimanche prochain ? Mais il faudrait qu’elles soient bien grasses et très, très bon marché, tu entends, ou je ne te les paierai pas... »

L’Indien accroupi devant sa hutte, tout à son travail, ne parut même pas remarquer la présence de M. Winthrop, encore moins sa curiosité. Pour ne pas paraître idiot, l’Américain finit par lui demander :

« Combien vendez-vous ces petits paniers, mon ami ?

- Cinquante centavitos, patroncito5, mon bon petit monsieur, répondit poliment l’Indien, Quatre reales6.

- Marché conclu, dit M. Winthrop.

Son ton et son geste eussent été les mêmes s’il avait acheté une compagnie de chemin de fer. Il ajouta, en examinant son achat :

- Je sais déjà à qui je vais donner cette jolie petite chose. Je me demande ce qu’elle en fera, mais je suis sûr qu’elle sera ravie... »

En fait, il s’était attendu à ce que l’Indien lui demandât trois ou quatre pesos – et lorsqu’il se rendit compte qu’il avait estimé l’objet à six fois sa valeur, il comprit du même coup quelles possibilités ce misérable village indien pouvait offrir à un promoteur aussi dynamique que lui.

Sans attendre, il se mit à tâter le terrain :

« Mon ami, dit-il, supposons un instant que je vous achète dix de ces petits paniers qui, bien sûr, n’ont aucune espèce d’utilité pratique... Si je vous en achetais dix, quel prix me feriez-vous ?

L’Indien réfléchit pendant quelques secondes, comme s’il calculait, et répondit :

- Si vous m’en achetez dix, je vous les laisserai à quarante-cinq centavos la pièce, señorito gentleman.

- Parfait, amigo. Et si je vous en achetais cent ?

L’Indien, sans quitter son travail des yeux et sans manifester la moindre émotion, répondit :

- Dans ce cas, je consentirais peut-être à vous les laisser à quarante centavitos. »

M. Winthrop acheta seize paniers – tous ceux que l’Indien avait à lui offrir ce jour-là.

Après avoir passé trois semaines au Mexique, M. Winthrop, convaincu qu’il connaissait le pays à fond, qu’il avait tout vu et savait tout de ses habitants, de leur caractère et de leur mode de vie, regagna ce bon vieux Nooyorg7 et fut heureux de se retrouver dans un pays civilisé.

Un jour, en allant déjeuner, il passa devant la vitrine d'un confiseur et, en la regardant, se rappela soudain les petits paniers qu'il avait achetés dans ce lointain village indien. Il alla prendre chez lui ceux qui lui restaient et les porta chez l'un des fabricants de confiserie les plus connus de la ville, à qui il dit :

« Regardez... Je suis en mesure de vous fournir une des plus originales et des plus artistiques boîtes à bonbons – si j'ose dire – que vous puissiez imaginer. Ces petits paniers seraient parfaits pour présenter des chocolats de luxe. Jetez-y un coup d'œil et dites-moi ce que vous en pensez ?

Le confiseur examina les paniers et les trouva parfaits – originaux, séduisants et de bon goût. Il se garda bien, toutefois, de manifester son enthousiasme avant d'en connaître le prix et de savoir s'il pourrait s'en assurer l'exclusivité. Il haussa les épaules et dit :

- Ma foi je ne sais pas trop... Ce n'est pas tout à fait ce que je cherche, mais nous pourrions essayer. Cela dépend du prix; bien entendu ; dans notre partie, l'emballage ne doit pas coûter plus cher que ce qu'il contient.

- Faites-moi une proposition, suggéra M. Winthrop

- Pourquoi ne pas me dire plutôt ce que vous en voulez ?

- Non, M. Kemple. Étant donné que c'est moi qui ai découvert les paniers et que je suis seul à savoir où en trouver d'autres, j'ai l'intention de les vendre au plus offrant. Je pense que vous me comprenez ?

- Très bien, dit le confiseur. Que le meilleur gagne... je vais en parler à mes associés. Venez me voir demain à la même heure, je vous ferai une offre...

Le lendemain, M. Kemple dit à M. Winthrop :

- Je serai franc, mon cher. Je suis capable de reconnaître l'art où il est : ces paniers sont de petites œuvres d'art, c'est incontestable. D'un autre côté, nous ne sommes pas, comme vous le savez, des marchands d'objets d'art et nous ne pouvons utiliser ces charmantes petites choses que comme emballage de fantaisie pour nos chocolats. De jolis emballages, mais des emballages quand même. Je vous fais donc l'offre suivante, à prendre ou à laisser : un dollar vingt-cinq la pièce, pas un cent de plus.

M. Winthrop eut un sursaut que le confiseur interpréta de travers, en sorte qu'il ajouta hâtivement :

- Très bien, très bien, ne vous énervez pas... Nous pourrons peut-être aller jusqu'à un dollar cinquante.

- Disons un dollar soixante-quinze, jeta M. Winthrop en s'épongeant le front.

- D'accord. Un dollar soixante-quinze, livraison à New York. Le transport à votre charge, les frais de douane à la nôtre. Marché conclu ?

- Marché conclu, dit M. Winthrop.

Il allait partir lorsque le confiseur ajouta :

- Il y a, bien sûr, une condition ; nous n'avons que faire de cent ou deux cents paniers de ce genre, le jeu n'en vaudrait pas la chandelle. Il nous en faut au moins dix mille, ou milles douzaines si vous préférez, et d'au moins douze modèles différents. Nous sommes bien d'accord là-dessus ?

- Je peux vous proposer soixante modèles différents.

- Tant mieux. Et vous êtes certains de pouvoir nous en livrer dix mille, disons début octobre ?

- Absolument, dit M. Winthrop, en signant le contrat. »

Pendant presque toute la durée du voyage, M. Winthrop, un bloc-notes et un crayon à la main, fit des calculs pour savoir combien cette affaire lui rapporterait.

« Résumons-nous, se dit-il à mi-voix... Bon sang, où est passé ce maudit crayon ? Ah, le voilà... Dix mille paniers représentent donc un bénéfice net de... quinze mille quatre cent quarante dollars... Doux Jésus ! Quinze mille billets dans la poche de papa... Cette République n'est pas tellement arriérée, après tout ! »

Il retrouva l'Indien accroupi devant son jacalito, comme s'il n'en avait pas bougé depuis leur première et unique rencontre.

« Buenas tardes, mi amigo ! Dit M. Winthrop. Comment allez-vous ?

L'Indien se leva, ôta son chapeau, s'inclina poliment et dit d'une voix douce :

- Soyez le bienvenu, patroncito. Je vais bien, merci. Muy buenas tardes. Cette maison et tout ce que je possède sont à votre disposition.

Sur quoi, il se rassit, ajoutant en manière d'excuse :

- Pedroneme8, patroncito, il faut que je profite de la lumière du jour. Bientôt, il fera nuit.

- Je vous amène une fameuse affaire, mon ami, dit M. Winthrop.

- Tant mieux, señor. Cela me fait plaisir.

- Il va devenir fou quand il saura ce que j'ai à lui offrir, se dit M. Winthrop, qui poursuivit tout haut :

- Pensez-vous pouvoir me faire mille de ces petits paniers ?

- Pourquoi pas, patroncito ? Si je peux en faire seize, je peux en faire mille.

- Parfait ! Pourriez-vous en faire cinq mille ?

- Bien sûr, señor.

- Bien. Et si je vous en demandais dix mille, que diriez-vous ? Et quel en serait le prix ?

- Je peux en faire autant que vous voudrez, señor. J'y suis très habile. Personne, dans tout cet État, n'y est aussi habile que moi.

- C'est bien ce que je pensais... Supposons donc que je vous en commande dix mille. Combien de temps pensez-vous qu'il vous faudrait pour me les fournir ?

L'Indien, sans interrompre son travail, pencha la tête d'un coté puis de l'autre, comme s'il calculait le nombre de jours ou de semaines que lui prendrait une telle entreprise. Au bout de plusieurs minutes, il dit lentement :

- Il me faudra pas mal de temps pour faire autant de paniers, patroncito. Voyez-vous, les fibres doivent être très sèches avant de pouvoir être utilisées, et pendant tout le temps où elles sèchent il faut les travailler et les traiter d'une manière spéciale pour qu'elles ne perdent pas leur souplesse, leur douceur et leur lustre naturel. Même sèches, elles doivent paraître fraîches, ou alors elles ressembleraient à de la paille. Ensuite, je dois récolter les plantes, les racines, les écorces et les insectes dont je tire mes teintures. Ça aussi, croyez-moi, ça prend beaucoup de temps. Les plantes doivent être cueillies quand la lune est favorable, ou alors elles ne donnent pas la couleur désirée. Les insectes aussi, il faut que je les recueille sur les plantes au bon moment et dans certaines conditions... Mais bien entendu, jefecito9, je peux vous faire autant de canastitas'10 que vous voulez, et même trois douzaines si vous le désirez – à condition que vous m'en laissiez le temps.

- Trois douzaines ? S'écria M. Winthrop en levant les bras au ciel. Trois douzaines ?

Il se demandait s'il rêvait. Il s'était attendu à voir l'indien devenir fou de joie en apprenant qu'il pourrait vendre dix mille paniers sans aller et porte en porte et sans se faire rabrouer comme un chien galeux... Il remit donc la question du prix sur le tapis, espérant pas là stimuler l'Indien :

- Vous m'avez dit que si je vous achetais cent paniers vous me les laisseriez à quarante centavos la pièce. C'est bien ça, mon ami.

- Exactement, jefecito.

- Bon, dit M. Winthrop en prenant son courage à deux mains. Dans ce cas, si je vous en commande mille, c'est-à-dire dix fois plus, quel prix me ferez-vous ?

Ce chiffre était trop élevé pour l'entendement de l'Indien. Pour la première fois depuis l'arrivée de M. Winthrop, il interrompit son travail et essaya de comprendre. Il hocha la tête à plusieurs reprises, regarda autour de lui, d'un air un peu égaré, comme s'il eût cherché de l'aide, et répondit finalement :

- Excusez-moi, jefecito, mais c'est très difficile à calculer. Si vous voulez bien revenez demain, je pense que je pourrai vous répondre. »

Le lendemain matin, lorsqu'il revint à la hutte, M. Winthrop demanda à l'Indien, sans même prendre la peine de lui dire bonjour :

« Alors, vous avez calculé votre prix pour dix mille paniers ?

- Si, patroncito. Mais croyez-moi, cela m'a demandé beaucoup de travail et de soucis, car je ne voudrais pas vous voler votre bon argent...

- Ça va, amigo, ça va, assez de salades... Votre prix ?

- Si je dois vous faire mille canastitas, je vous les vendrai trois pesos chacun. Si je dois vous en faire cinq mille, ce sera neuf pesos. Et si vous en voulez dix mille, je ne pourrai vous les laisser à moins de quinze pesos la pièce.

Il se remit aussitôt au travail, comme s'il estimait avoir déjà perdu assez de temps en bavardages inutiles.

M. Winthrop pensa que sa méconnaissance de l'espagnol lui jouait un mauvais tour.

- Vous avez bien dit quinze pesos la pièce si je vous en achète dix mille ?

- Exactement, patroncito.

- Mais voyons, mon brave, ce n'est pas possible ! Je suis votre ami et je suis ici pour vous venir en aide !

- Je le sais, patroncito, et je vous en remercie.

- Bon. Dans ce cas, essayons de parler calmement... Ne m'avez-vous pas dit que si je vous achetais cent paniers, vous me les laisseriez à quarante centavos la pièce ?

- Si, jefecito, c'est bien ce que j'ai dit. Si vous m'en achetiez cent, je vous les vendrais quarante centavos – à condition d'en avoir cent, ce qui n'est malheureusement pas le cas.

- Très bien dit M. Winthrop qui avait l'impression de perdre la raison... Ce que je ne comprends pas, alors, c'est pourquoi vous ne pouvez pas me faire le même prix si je vous en commande dix mille ! Je ne veux pas marchander inutilement, ce n'est pas mon genre... Mais enfin, si vous pouvez me les vendre quarante centavos, que j'en prenne vingt, cinquante ou cent, pourquoi augmenter à ce point votre prix si je vous en prends plus de cent ?

- Bueno, patroncito, c'est pourtant facile à comprendre, mille canastitas me demandent cent fois plus de travail que dix, et dix mille me demanderaient tant de travail et de temps que je ne pourrais jamais les finir, pas même en un siècle. Pour faire mille canastitas, il me faut plus de fibres que pour cent et plus de plantes, de racines, d'écorces et d'insectes pour les teintures. Il ne suffit pas d'aller dans la forêt et de se baisser, croyez-moi : il me faut parfois marcher quatre ou cinq jours avant de trouver une racine qui me donne le bleu-violet que je désire. Et puis, si je dois faire autant de paniers, qui s'occupera de mon maïs, de mes haricots, de mes chèvres ? Qui me tuera un lapin de temps en temps, pour agrémenter mon repas du dimanche ? Si je n'ai pas de maïs, je n'aurai pas de tortillas à manger, et si je ne soigne pas mes haricots, comment aurais-je des frijoles ?

- Mais je vous donnerai tant d'argent pour vos paniers que vous pourrez achetez plus de maïs et de haricots que vous en pourriez désirer !

- C'est vous qui le dites, señorito ! Voyez-vous, je ne peux compter que sur le maïs que je cultive moi-même. Celui que d'autres cultiveront ou non, je ne suis pas certain de pouvoir le manger...

- N'avez-vous pas dans ce village des parents qui pourraient vous aider à faire ces paniers ?

- J'ai des tas de parents dans ce village. En fait, tout le monde ici est un peu mon parent.

- Mais alors, les autres ne peuvent-ils pas cultiver votre champ et veiller sur vos chèvres pendant que vous ferez des paniers pour moi ? Mieux encore : ils pourraient récolter à votre place les fibres et les plantes dont vous avez besoin et vous aider à les préparer...

- Ils le pourraient, patroncito, oui, bien sûr. Mais alors qui s'occuperait de leurs champs et de leurs bêtes ? S'ils m'aidaient comme vous le dites, plus personne ne travaillerait la terre, et le prix du maïs et des haricots monterait au point qu'aucun d'entre nous ne pourrait en acheter, et nous mourrions tous de faim ! Et si le prix des choses continuait à monter, comment pourrais-je faire des paniers à quarante centavos la pièce ? Une pincée de sel ou un seul chile vert me coûterait plus cher que le prix d'un panier... Vous voyez bien, très estimé caballero, que si je dois vous faire autant de paniers, je ne peux vraiment pas vous les vendre moins de quinze pesos chacun !

M. Winthrop était tenace en affaires, ce qui n'était pas surprenant étant donné la ville d'où il venait. Il se refusait d'autant plus à abandonner la partie qu'il sentait quinze mille dollars en train de lui échapper. Avec une espèce de désespoir, il discuta et marchanda avec l'Indien pendant près de deux heures, essayant de lui faire comprendre les raisons qu'il avait de ne pas laisser échapper la grande chance de sa vie. L'indien, pendant ce temps, continuait de faire ses paniers.

- Rendez-vous compte, mon brave, dit M. Winthrop : une telle occasion ne se représentera sans doute jamais à vous ! Laissez-moi vous expliquer, noir sur blanc, la fortune que vous laisseriez échapper en me faisant faux bond...

Il arracha un feuillet, puis un autre, de son bloc-notes, les couvrit de chiffres, démontra au paysan qu'il pouvait devenir l'homme le plus riche de tout le district. L'indien, sans répondre, le regardait faire avec une expression de sincère admiration : il lui semblait prodigieux que l'on pût faire, aussi vite, des multiplications, des divisions et des soustractions aussi compliquées.

L'américain remarqua l'intérêt croissant de l'Indien, mais se méprit sur sa signification.

- Voilà où vous en êtes, amigo, dit-il : si vous faites ce que je vous demande, vous aurez un compte en banque de quatre mille pesos exactement ! Et pour vous montrer que je suis vraiment votre ami, je suis prêt à arrondir la somme à cinq mille pesos tous en argent.

Mais l'Indien n'avait pas un seul instant prêté attention à ce que disait M . Winthrop. Une telle somme d'argent n'avait pour lui aucune espèce de signification. Il ne s'était intéressé qu'à la rapidité avec laquelle M. Winthrop calculait et alignait les chiffres.

- Alors, qu'en dites-vous ? Marché conclu ? Dites oui et je vous verse une avance à l'instant même.

- Je vous ai déjà répondu, patroncito : le prix est de quinze pesos la pièce.

- Mais, bon sang, s'écria M. Winthrop d'un ton désespéré, vous n'avez donc rien compris ? Vous vous obstinez à me faire le même prix !

- Oui, patroncito, répondit l'Indien avec détachement. C'est le même prix parce que je ne peux pas vous en faire un autre... Il y a d'ailleurs autre chose que vous ne savez peut-être pas, señor : ces canastitas, voyez-vous, il faut que je les fasse à ma manière, en y mettant ma chanson et en y tressant de petits morceaux de mon âme. Si je devais en faire autant que vous en voulez, je ne pourrais plus mettre mon âme et mes chansons dans chacun d'eux. Chacun ressemblerait exactement aux autres, et cela me briserait peu à peu le coeur. Il faut que chacun de mes paniers soit une chanson différente, que j'entends le matin lorsque le soleil se lève, lorsque les oiseaux s'éveillent et lorsque les papillons viennent se poser sur eux. Il le faut, parce que les papillons aiment mes paniers et leurs jolies couleurs, et c'est pour cela qu'ils viennent se poser sur eux, et c'est en les regardant que j'imagine de nouvelles canastitas... Là-dessus, señor jefecito, si vous voulez bien m'excuser, je vais me remettre au travail. J'ai déjà perdu beaucoup de temps, même si c'est un plaisir et un grand honneur pour moi d'écouter parler un caballero de votre qualité. Mais après-demain, c'est jour de marché à la ville, et il faut que j'aie des paniers à vendre. Merci de votre visite, señor, et adios... »

Et c'est ainsi qu'il fut épargné aux poubelles américaines de devenir le cimetière de petites canastitas multicolores, vides, déchirées et chiffonnées, de ces petits paniers où un Indien du Mexique avait tressé les rêves de son âme et les sanglots de son coeur – ses poèmes silencieux.

B. Traven, Chaîne de montage dans Le Visiteur du soir et autres histoires, traduction C. Elsen.

Notes et références- « Le Rotary » et « le Lions » sont des clubs regroupant des gens aisés dans le but d’entreprendre des actions souvent humanitaires.

- Petit village.

- Paille qui sert à tresser les nattes sur lesquelles dorment les indiens.

- Le meilleur.

- Petit patron, marque le respect de l’Indien.

- Le centavo est le centime du peso, le suffixe –ito est diminutif. Huit reales font un peso.

- Traven moque ici la prononciation new-yorkaise de M. Winthrop.

- Excusez-moi.

- « Petit chef », marque de respect.

- Petits paniers.

1966

Mr. E. L. Winthrop of New York was on vacation in the Republic of Mexico. It wasn't long before he realized that this strange and really wild country had not yet been fully and satisfactorily explored by Rotarians and Lions, who are forever conscious of their glorious mission on earth. Therefore, he considered it his duty as a good American citizen to do his part in correcting this oversight.

In search for opportunities to indulge in his new avocation, he left the beaten track and ventured into regions not especially mentioned, and hence not recommended, by travel agents to foreign tourists. So it happened that one day he found himself in a little, quaint Indian village somewhere in the State of Oaxaca.

Walking along the dusty main street of this pueblecito, which knew nothing of pavements, drainage, plumbing, or of any means of artificial light save candles or pine splinters, he met with an Indian squatting on the earthen-floor front porch of a palm hut, a so-called jacalito.

The Indian was busy making little baskets from bast and from all kinds of fibers gathered by him in the immense tropical bush which surrounded the village on all sides. The material used had not only been well prepared for its purpose but was also richly colored with dyes that the basket-maker himself extracted from various native plants, barks, roots and from certain insects by a process known only to him and the members of his family.

His principal business, however, was not producing baskets. He was a peasant who lived on what the small property he possessed--less than fifteen acres of not too fertile soil--would yield, after much sweat and labor and after constantly worrying over the most wanted and best suited distribution of rain, sunshine, and wind and the changing balance of birds and insects beneficial or harmful to his crops. Baskets he made when there was nothing else for him to do in the fields, because he was unable to dawdle. After all, the sale of his baskets, though to a rather limited degree only, added to the small income he received from his little farm.

In spite of being by profession just a plain peasant, it was clearly seen from the small baskets he made that at heart he was an artist, a true and accomplished artist. Each basket looked as if covered all over with the most beautiful sometimes fantastic ornaments, flowers, butterflies, birds, squirrels, antelope, tigers, and a score of other animals of the wilds. Yet, the most amazing thing was that these decorations, all of them symphonies of color, were not painted on the baskets but were instead actually part of the baskets themselves. Bast and fibers dyed in dozens of different colors were so cleverly--one must actually say intrinsically-- interwoven that those attractive designs appeared on the inner part of the basket as well as on the outside. Not by painting but by weaving were those highly artistic effects achieved. This performance he accomplished without ever looking at any sketch or pattern. While working on a basket these designs came to light as if by magic, and as long as a basket was not entirely finished one could perceive what in this case or that the decoration would be like.

People in the market town who bought these baskets would use them for sewing baskets or to decorate tables with or window sills, or to hold little things to keep them from lying around. Women put their jewelry in them or flowers or little dolls. There were in fact a hundred and two ways they might serve certain purposes in a household or in a lady's own room.

Whenever the Indian had finished about twenty of the baskets he took them to town on market day. Sometimes he would already be on his way shortly after midnight because he owned only a burro to ride on, and if the burro had gone astray the day before, as happened frequently, he would have to walk the whole way to town and back again.

At the market he had to pay twenty centavos in taxes to sell his wares. Each basket cost him between twenty and thirty hours of constant work, not counting the time spent gathering bast and fibers, preparing them, making dyes and coloring the bast. All this meant extra time and work. The price he asked for each basket was fifty centavos, the equivalent of about four cents. It seldom happened, however, that a buyer paid outright the full fifty centavos asked--or four reales as the Indian called that money. The prospective buyer started bargaining, telling the Indian that he ought to be ashamed to ask such a sinful price. "Why, the whole dirty thing is nothing but ordinary petate straw which you find in heaps wherever you may look for it; the jungle is packed full of it," the buyer would argue. "Such a little basket, what's it good for anyhow? If I paid you, you thief, ten centavitos for it you should be grateful and kiss my hand. Well, it's your lucky day, I'll be generous this time, I'll pay you twenty, yet not one green centavo more. Take it or run along."

So he sold finally for twenty-five centavos, but then the buyer would say, "Now, what do you think of that? I've got only twenty centavos change on me. What can we do about that? If you can change me a twenty-peso bill, all right, you shall have your twenty-five fierros." Of course, the Indian could not change a twenty-peso bill and so the basket went for twenty centavos.

He had little if any knowledge of the outside world or he would have known that what happened to him was happening every hour of every day to every artist all over the world. That knowledge would perhaps have made him very proud, because he would have realized that he belonged to the little army which is the salt of the earth and which keeps culture, urbanity and beauty for their own sake from passing away.

Often it was not possible for him to sell all the baskets he had brought to market, for people here as elsewhere in the world preferred things made by the millions and each so much like the other that you were unable, even with the help of a magnifying glass, to tell which was which and where was the difference between two of the same kind.

Yet he, this craftsman, had in his life made several hundreds of those exquisite baskets, but so far no two of them had he ever turned out alike in design. Each was an individual piece of art and as different from the other as was a Murillo from a Velásquez.

Naturally he did not want to take those baskets which he could not sell at the market place home with him again if he could help it. In such a case he went peddling his products from door to door where he was treated partly as a beggar and partly as a vagrant apparently looking for an opportunity to steal, and he frequently had to swallow all sorts of insults and nasty remarks.

Then, after a long run, perhaps a woman would finally stop him, take one of the baskets and offer him ten centavos, which price through talks and talks would perhaps go up to fifteen or even to twenty. Nevertheless, in many instances he would actually get no more than just ten centavos, and the buyer, usually a woman, would grasp that little marvel and right before his eyes throw it carelessly upon the nearest table as if to say, "Well, I take that piece of nonsense only for charity's sake. I know my money is wasted. But then, after all, I'm a Christian and I can't see a poor Indian die of hunger since he has come such a long way from his village." This would remind her of something better and she would hold him and say, "Where are you at home anyway, Indito? What's your pueblo? So, from Huehuetonoc? Now, listen here, Indito, can't you bring me next Saturday two or three turkeys from Huehuetonoc? But they must be heavy and fat and very, very cheap or I won't even touch them. If I wish to pay the regular price I don't need you to bring them. Understand? Hop along, now, Indito."

The Indian squatted on the earthen floor in the portico of his hut, attended to his work and showed no special interest in the curiosity of Mr. Winthrop watching him. He acted almost as if he ignored the presence of the American altogether.

"How much that little basket, friend?" Mr. Winthrop asked when he felt that he at least had to say something as not to appear idiotic.

"Fifty centavitos, patroncito, my good little lordy, four reales," the Indian answered politely.

"All right, sold," Mr. Winthrop blurted out in a tone and with a wide gesture as if he had bought a whole railroad. And examining his buy he added, "I know already who I'll give that pretty little thing to. She'll kiss me for it, sure. Wonder what she'll use it for?"

He had expected to hear a price of three or even four pesos. The moment he realized that he had judged the value six times too high, he saw right away what great business possibilities this miserable Indian village might offer to a dynamic promoter Eke himself. Without further delay he started exploring those possibilities. "Suppose, my good friend, I buy ten of these little baskets of yours which, as I might as well admit right here and now, have practically no real use whatsoever. Well, as I was saying, if I buy ten, how much would you then charge me apiece?"

The Indian hesitated for a few seconds as if making calculations. Finally he said, "If you buy ten I can let you have them for forty-five centavos each, señorita gentleman."

"All right, amigo. And now, let's suppose I buy from you straight away one hundred of these absolutely useless baskets, how much will cost me each?"

The Indian, never fully looking up to the American standing before him and hardly taking his eyes off his work, said politely and without the slightest trace of enthusiasm in his voice, "In such a case I might not be quite unwilling to sell each for forty centavitos."

Mr. Winthrop bought sixteen baskets, which was all the Indian had in

stock.

After three weeks' stay in the Republic, Mr. Winthrop was convinced that he knew this country perfectly, that he had seen everything and knew all about the inhabitants, their character and their way of life, and that there was nothing left for him to explore. So he returned to good old Nooyorg and felt happy to be once more in a civilized country, as he expressed it to himself.

One day going out for lunch he passed a confectioner's and, looking at the display in the window, he suddenly remembered the little baskets he had bought in that faraway Indian village.

He hurried home and took all the baskets he still had left to one of the best-known candy-makers in the city.

"I can offer you here," Mr. Winthrop said to the confectioner, "one of the most artistic and at the same time the most original of boxes, if you wish to call them that. These little baskets would be just right for the most expensive chocolates meant for elegant and high-priced gifts. Just have a good look at them, Sir, and let me listen."

The confectioner examined the baskets and found them extraordinarily well suited for a certain fine in his business. Never before had there been anything like them for originality, prettiness and good taste. He, however, avoided most carefully showing any sign of enthusiasm, for which there would be time enough once he knew the price and whether he could get a whole load exclusively.

He shrugged his shoulders and said, "Well, I don't know. If you asked me I'd say it isn't quite what I'm after. However, we might give it a try. It depends, of course, on the price. In our business the package mustn't cost more than what's in it."

"Do I hear an offer?" Mr. Winthrop asked.

"Why don't you tell me in round figures how much you want for them? I'm not good in guessing."

"Well, I'll tell you, Mr. Kemple: since I'm the smart guy who discovered these baskets and since I'm the only Jack who knows where to lay his hands on more, I'm selling to the highest bidder, on an exclusive basis, of course. I'm positive you can see it my way, Mr. Kemple."

"Quite so, and may the best man win," the confectioner said. "I'll talk the matter over with my partners. See me tomorrow same time, please, and I'll let you know how far we might be willing to go."

Next day when both gentlemen met again Mr. Kemple said: "Now, to be frank with you, I know art on seeing it, no getting around that. And these baskets are little works of art, they surely are. However, we are no art dealers, you realize that of course. We've no other use for these pretty little things except as fancy packing for our French pralines made by us. We can't pay for them what we might pay considering them pieces of art. After all to us they're only wrappings. Fine wrappings, perhaps, but nevertheless wrappings. You'll see it our way I hope, Mr. oh yes, Mr. Winthrop. So, here is our offer, take it or leave it: a dollar and a quarter apiece and not one cent more."

Mr. Winthrop made a gesture as if he had been struck over the head.

The confectioner, misunderstanding this involuntary gesture of Mr. Winthrop, added quickly, "All right, all right, no reason to get excited, no reason at all. Perhaps we can do a trifle better. Let's say one-fifty."

"Make it one-seventy-five," Mr. Winthrop snapped, swallowing his breath while wiping his forehead.

"Sold. One-seventy-five apiece free at port of New York. We pay the customs and you pay the shipping. Right? "

"Sold," Mr. Winthrop said also and the deal was closed.

"There is, of course, one condition," the confectioner explained just when Mr. Winthrop was to leave. "One or two hundred won't do for us. It wouldn't pay the trouble and the advertising. I won't consider less than ten thousand, or one thousand dozens if that sounds better in your ears. And they must come in no less than twelve different patterns well assorted. How about that?"

"I can make it sixty different patterns or designs."

"So much the better. And you're sure you can deliver ten thousand let's say early October?"

"Absolutely," Mr. Winthrop avowed and signed the contract.

Practically all the way back to Mexico, Mr. Winthrop had a notebook in his left hand and a pencil in his right and he was writing figures, long rows of them, to find out exactly how much richer he would be when this business had been put through.

"Now, let's sum up the whole goddamn thing," he muttered to himself. "Damn it, where is that cursed pencil again? I had it right between my fingers. Ah, there it is. Ten thousand he ordered. Well, well, there we got a clean-cut profit of fifteen thousand four hundred and forty genuine dollars. Sweet smackers. Fifteen grand right into papa's pocket. Come to think of it, that Republic isn't so backward after all."

"Buenas tardes, mi amigo, how are you?" he greeted the Indian whom he found squatting in the porch of his jacalito as if he had never moved from his place since Mr. Winthrop had left for New York.

The Indian rose, took off his hat, bowed politely and said in his soft voice, "Be welcome, patroncito. Thank you, I feel fine, thank you. Muy buenas tardes. This house and all I have is at your kind disposal." He bowed once more, moved his right hand in a gesture of greeting and sat down again. But he excused himself for doing so by saying, "Perdoneme, patroncito, I have to take advantage of the daylight, soon it will be night."

"I've got big business for you, my friend," Mr. Winthrop began.

"Good to hear that, señor."

Mr. Winthrop said to himself, "Now, he'll jump up and go wild when he learns what I've got for him." And aloud he said: "Do you think you can make me one thousand of these little baskets?"

"Why not, patroncito? If I can make sixteen, I can make one thousand also."

"That's right, my good man. Can you also make five thousand? "

"Of course, señor. I can make five thousand if I can make one thousand."

"Good. Now, if I should ask you to make me ten thousand, what would you say? And what would be the price of each? You can make ten thousand, can't you?"

"Of course, I can, señor. I can make as many as you wish. You see, I am an expert in this sort of work. No one else in the whole state can make them the way I do."

"That's what I thought and that's exactly why I came to you."

"Thank you for the honor, patroncito."

"Suppose I order you to make me ten thousand of these baskets, how much time do you think you would need to deliver them?"

The Indian, without interrupting his work, cocked his head to one side and then to the other as if he were counting the days or weeks it would cost him to make all these baskets.

After a few minutes he said in a slow voice, "It will take a good long time to make so many baskets, patroncito. You see, the bast and the fibers must be very dry before they can be used properly. Then all during the time they are slowly drying, they must be worked and handled in a very special way so that while drying they won't lose their softness and their flexibility and their natural brilliance. Even when dry they must look fresh. They must never lose their natural properties or they will look just as lifeless and dull as straw. Then while they are drying up I got to get the plants and roots and barks and insects from which I brew the dyes. That takes much time also, believe me. The plants must be gathered when the moon is just right or they won't give the right color. The insects I pick from the plants must also be gathered at the right time and under the right conditions or else they produce no rich colors and are just like dust. But, of course, jefecito, I can make as many of these canastitas as you wish, even as many as three dozens if you want them. Only give me time."

"Three dozens? Three dozens?" Mr. Winthrop yelled, and threw up both arms in desperation. "Three dozens!" he repeated as if he had to say it many times in his own voice so as to understand the real meaning of it, because for a while he thought that he was dreaming. He had expected the Indian to go crazy on hearing that he was to sell ten thousand of his baskets without having to peddle them from door to door and be treated like a dog with a skin disease.

So the American took up the question of price again, by which he hoped to activate the Indian's ambition. "You told me that if I take one hundred baskets you will let me have them for forty centavos apiece. Is that right, my friend?"

"Quite right, jefecito."

"Now," Mr. Winthrop took a deep breath, "now, then, if I ask you to make me one thousand, that is, ten times one hundred baskets, how much will they cost me, each basket?"

That figure was too high for the Indian to grasp. He became slightly confused and for the first time since Mr. Winthrop had arrived he interrupted his work and tried to think it out. Several times he shook his head and looked vaguely around as if for help. Finally he said, "Excuse me, jefecito, little chief, that is by far too much for me to count. Tomorrow, if you will do me the honor, come and see me again and I think I shall have my answer ready for you, patroncito."

When on the next morning Mr. Winthrop came to the hut he found the Indian as usual squatting on the floor under the overhanging palm roof working at his baskets.

"Have you got the price for ten thousand?" he asked the Indian the very moment he saw him, without taking the trouble to say "Good Morning!"

"SL patroncito, I have the price ready. You may believe me when I say it has cost me much labor and worry to find out the exact price, because, you see, I do not wish to cheat you out of your honest money."

"Skip that, amigo. Come out with the salad. What's the, price?" Mr. Winthrop asked nervously.

"The price is well calculated now without any mistake on my side. If I got to make one thousand canastitas each will be three pesos. If I must make five thousand, each will cost nine pesos. And if I have to make ten thousand, in such a case I can't make them for less than fifteen pesos each." Immediately he returned to his work as if he were afraid of losing too much time with such idle talk.

Mr. Winthrop thought that perhaps it was his faulty knowledge of this foreign language that had played a trick on him.

"Did I hear you say fifteen pesos each if I eventually would buy ten thousand?"

"That's exactly and without any mistake what I've said, patroncito," the Indian answered in his soft courteous voice.

"But now, see here, my good man, you can't do this to me. I'm your friend and I want to help you get on your feet."

"Yes, patroncito, I know this and I don't doubt any of your words."

"Now, let's be patient and talk this over quietly as man to man. Didn't you tell me that if I would buy one hundred you would sell each for forty centavos?"

"Si, jefecito, that's what I said. If you buy one hundred you can have them for forty centavos apiece, provided that I have one hundred, which I don't."

"Yes, yes, I see that." Mr. Winthrop felt as if he would go insane any minute now. "Yes, so you said. Only what I can't comprehend is why you cannot sell at the same price if you make me ten thousand. I certainly don't wish to chisel on the price. I am not that kind. Only, well, let's see now, if you can sell for forty centavos at all, be it for twenty or fifty or a hundred, I can't quite get the idea why the price has to jump that high if I buy more than a hundred."

"Bueno, patroncito, what is there so difficult to understand? It'sall very simple. One thousand canastitas cost me a hundred times more work than a dozen. Ten thousand cost me so much time and labor that I could never finish them, not even in a hundred years. For a thousand canastitas I need more bast than for a hundred, and I need more little red beetles and more plants and roots and bark for the dyes. It isn't that you just can walk into the bush and pick all the things you need at your heart's desire. One root with the true violet blue may cost me four or five days until I can find one in the jungle. And have you thought how much time it costs and how much hard work to prepare the bast and fibers? What is more, if I must make so many baskets, who then will look after my corn and my beans and my goats and chase for me occasionally a rabbit for meat on Sunday? If I have no corn, then I have no tortillas to eat, and if I grow no beans, where do I get my frijoles from?"

'Tut since you'll get so much money from me for your baskets you can buy all the corn and beans in the world and more than you need."

"That's what you think, señorito, little lordy. But you see, it is only the corn I grow myself that I am sure of. Of the corn which others may or may not grow, I cannot be sure to feast upon."

"Haven't you got some relatives here 'm this village who might help you to make baskets for me?" Mr. Winthrop asked hopefully.

"Practically the whole village is related to me somehow or other. Fact is, I got lots of close relatives in this here place."

"Why then can't they cultivate your fields and look after your goats while you make baskets for me? Not only this, they might gather for you the fibers and the colors in the bush and lend you a hand here and there in preparing the material you need for the baskets."

"They might, patroncito, yes, they might. Possible. But then you see who would take care of their fields and cattle if they work for me? And if they help me with the baskets it turns out the same. No one would any longer work his fields properly. In such a case corn and beam would get up so high in price that none of us could buy any and we all would starve to death. Besides, as the price of everything would rise and rise higher still how could I make baskets at forty centavos apiece? A pinch of salt or one green chili would set me back more than I'd collect for one single basket. Now you'll understand, highly estimated caballero and jefecito, why I can't make the baskets any cheaper than fifteen pesos each if I got to make that many."

Mr. Winthrop was hard-boiled, no wonder considering the city he came from. He refused to give up the more than fifteen thousand dollars which at that moment seemed to slip through his fingers like nothing. Being really desperate now, he talked and bargained with the Indian for almost two full hours, trying to make him understand how rich he, the Indian, would become if he would take this greatest opportunity of his life.

The Indian never ceased working on his baskets while he explained his points of view.

"You know, my good man," Mr. Winthrop said, "such a wonderful chance might never again knock on your door, do you realize that? Let me explain to you in ice-cold figures what fortune you might miss if you leave me flat on this deal."

He tore out leaf after leaf from his notebook, covered each with figures and still more figures, and while doing so told the peasant he would be the richest man in the whole district.

The Indian without answering watched with a genuine expression of awe as Mr. Winthrop wrote down these long figures, executing complicated multiplications and divisions and subtractions so rapidly that it seemed to him the greatest miracle he had ever seen.

The American, noting this growing interest in the Indian, misjudged the real significance of it "There you are, my friend," he said. "That's exactly how rich you're going to be. You'll have a bankroll of exactly four thousand pesos. And to show you that I'm a real friend of yours, I'll throw in a bonus. I'll make it a round five thousand pesos, and all in silver."

The Indian, however, had not for one moment thought of four thousand pesos. Such an amount of money had no meaning to him. He had been interested solely in Mr. Winthrop's ability to write figures so rapidly.

"So, what do you say now? Is it a deal or is it? Say yes and you'll get your advance this very minute."

"As I have explained before, patroncito, the price is fifteen pesos each."

"But, my good man," Mr. Winthrop shouted at the poor Indian in utter despair, "where have you been all this time? On the moon or where? You are still at the same price as before."

"Yes, I know that, jefecito, my little chief," the Indian answered, entirely unconcerned. "It must be the same price because I cannot make any other one. Besides, señor, there's still another thing which perhaps you don't know. You see, my good lordy and caballero, I've to make these canastitas my own way and with my song in them and with bits of my soul woven into them. If I were to make them in great numbers there would no longer be my soul in each, or my songs. Each would look like the other with no difference whatever and such a thing would slowly eat up my heart. Each has to be another song which I hear in the morning when the sun rises and when the birds begin to chirp and the butterflies come and sit down on my baskets so that I may see a new beauty, because, you see, the butterflies like my baskets and the pretty colors on them, that's why they come and sit down, and I can make my canastitas after them. And now, señor jefecito, if you will kindly excuse me, I have wasted much time already, although it was a pleasure and a great honor to hear the talk of such a distinguished caballero like you. But I'm afraid I've to attend to my work now, for day after tomorrow is market day in town and I got to take my baskets there. Thank you, señor, for your visit. Adiós."

And in this way it happened that American garbage cans escaped the fate of being turned into receptacles for empty, torn, and crumpled little multicolored canastitas into which an Indian of Mexico had woven dreams of his soul, throbs of his heart: his unsung poems.

B. Traven Assembly Line in The Nigtht Visitor and Other Stories::::::::::::::::

a gift :

::::::::::::::::

Happiness

So early it's still almost dark out.

I'm near the window with coffee,

and the usual early morning stuff

that passes for thought.

When I see the boy and his friend

walking up the road

to deliver the newspaper.

They wear caps and sweaters,

and one boy has a bag over his shoulder.

They are so happy

they aren't saying anything, these boys.

I think if they could, they would take

each other's arm.

It's early in the morning,

and they are doing this thing together.

They come on, slowly.

The sky is taking on light,

though the moon still hangs pale over the water.

Such beauty that for a minute

death and ambition, even love,

doesn't enter into this.

Happiness. It comes on

unexpectedly. And goes beyond, really,

any early morning talk about it.